When the government isn’t shut down, courts and legislatures work together to make it happen. Public policy scholar Scott Barclay explains.

Late this summer, a few short weeks after the US Supreme Court made landmark rulings on gay rights and affirmative action, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg offered publicly a remarkable insight on the role of courts in the political process. She said it not within the confines of an opinion in one of those landmark court cases this summer but instead in one of her rare interviews with a newspaper. She noted that “in so many instances, the court and Congress have been having conversations with each other, particularly recently in the civil rights area,” she said. “So it isn’t good when you have a Congress that can’t react.” (Associate Justice Ginsburg, quoted in the New York Times, August 24, 2013)

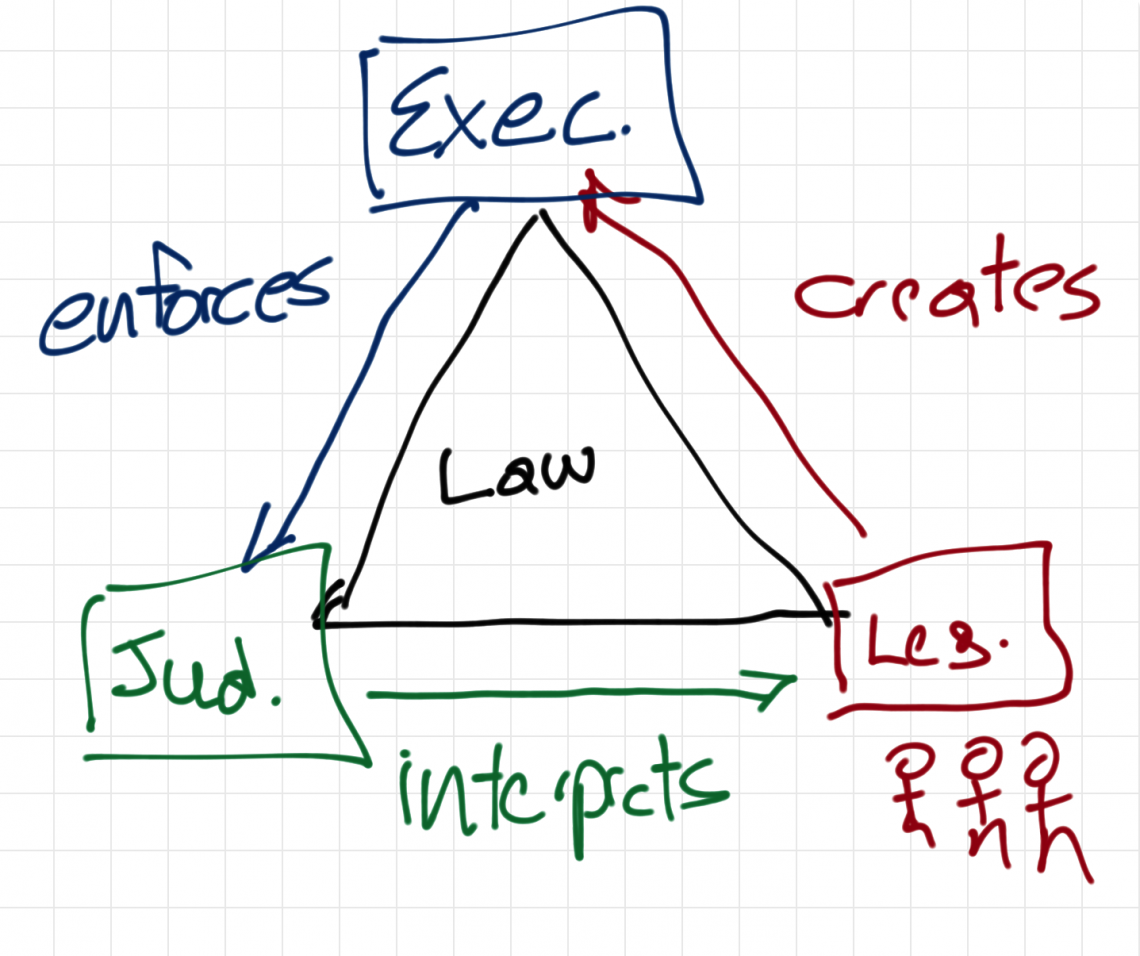

It is an important insight. We often tend to think of federal and state courts as either a) passively enacting laws written by Congress or state legislatures, respectively, or b) acting to actively contradict Congressional or state legislative goals in order correct constitutional wrongs to groups or individuals brought about by legislative zeal around a particular policy topic. These two posited roles are in apparent contradiction. As passive enactors of policies, courts become positioned similar to bureaucratic agencies: there simply to ensure effective policy implementation within the larger policy goals set by the legislature. As the fixer of constitutional wrongs, courts become positioned in direct conflict with the legislature: adopting the constitutional power to review, reject and hence thwart defined legislative goals.

Justice Ginsburg reminds us that neither of these posited roles are the full story. Instead, she invites us to think of legislatures as ongoing partners with the courts in a dynamic “conversation” as the two institutions, among others, negotiate the implementation of a policy and the appropriate means for resolving policy problems that arise along the way. As long ago noted by political scientists and legal scholars, courts often become unwittingly drawn into this ongoing conversation by the fact that legislatures, in order to achieve the legislative majorities necessary to pass laws, are apt to leave key details of many policies purposely vague. Accordingly, the determination of a policy’s actual application in real-life situations often, but not always, tends to end up before judges faced with defining its realization for bureaucratic agencies and the individuals before them who are now impacted by those agencies’ implementation of the policy. Therefore, it often becomes the judges themselves, rather than legislatures, who manage to finally bring coherence and consistency to many previously enacted policies.

More importantly, policies themselves rarely spring full cloth into being, especially those that seek to transform existing behavior or existing attitudes, as much of the civil rights-related policies seek to do. In such cases, policies emerge from a long engagement with the issues by social movements, courts, legislatures, and the public. The full meaning of a policy only slowly emerges as these institutions negotiate not only what each policy actor wants, but also what they can accept in order to think of the issue as resolved and settled. In addition, these institutions, and the related government agencies usually responsible for the on-the-ground implementation, often take time to come to terms with the necessary practicalities of changing existing rules, existing practices, existing relationships, and existing norms.

In my own area of research—lesbian and gay rights—this interplay of institutions has consistently been on display since this issue emerged onto the policy agenda in 1971. As of September 2013, nineteen separate states (CA, CO, CT, DE, HI, IA, IL, MA, MD, ME, MN, NH, NJ, NY, NV, OR, RI, VT, and WA), have introduced either marriage or civil unions for same sex couples. This current result has been achieved in one of three ways: 1) a state’s legislature successfully passed a bill though both legislatives houses in support of same sex marriage or civil unions, and the state’s governor signed it into law; 2) a state’s highest court judicially ordered the establishment of same sex marriage and/or civil unions; or 3) a statewide popular initiative introduced same sex marriage or civil unions.

But, in truth, in most states it has been achieved by a combination of at least two of these methods over time. For example, in Vermont, the state’s highest court in 1999 ruled in support of inclusion of same sex couples into the state’s scheme of benefits and obligation associated with marriage. In 2000, the state’s legislature introduced Civil Unions in response to this directive from the court. While meeting the criteria established by the court, this legislative policy solution did not seem to satisfy social movements, many legislators, or the general public. In 2009, the state’s legislature introduced marriage for same sex couples, in a move that replaces existing Civil Unions. Similarly, in Connecticut, the state’s legislature acted in 2005 to introduce Civil Unions in part to pre-empt an expected judicial decision on marriage equality. And, in response to this legislative recognition of the rights of same sex couples, the state’s highest court acted in 2008 to introduce marriage for such couples.

A clear pattern of legislative and judicial back-and-forth is also very evident in a last decade of policy actions around same sex marriage in California, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Washington.

And, just as Justice Ginsburg lamented the effective absence of her Congressional colleagues in some of these ongoing policy “conversations,” it has been clear in my own research that state courts have often welcomed and invited the input of state legislatures as they shape the actual application of future policies around same sex marriage. Courts have delayed judicial decisions as they await the chance of legislative—rather than judicial—determination of the look of a policy. In New York, courts explicitly returned the decision of whether same sex marriages should exist to the recalcitrant legislature. In Vermont, New Jersey, and elsewhere, courts initially allowed legislatures to determine the choice of form: civil unions or marriage.

This interplay is not the popular image of how rights are achieved: the edict brought from constitutional powers on high, as the myth of Brown v Board of Education would have us believe. But, in fact, it is the more historically accurate version. Brown was largely implemented through the actions by federal bureaucratic agencies who took their policy lead from congressional actions and ongoing court decisions that determined the look of the policy on-the-ground. Similarly, notwithstanding the US Supreme Court intervention in 2003 in Lawrence v Texas, the elimination of state sodomy prohibitions from the 1962 through 2003 occurred through a dynamic mix of state legislative action and state court decisions, before federal court action finally completed the task.

Such an understanding, as offered by Justice Ginsburg, helps us situate the court actions that are presently unfolding in New Mexico, Pennsylvania and elsewhere around marriage equality. Equally important, it helps us better understand the role of courts in the democratic process. As both a scholar and a citizen, I find that interplay both fascinating and reassuring in a democratic system.

Photo: Hawaiiesquire