Paul Butler grew up in a black neighborhood on the Southside of Chicago. He was a smart, talented kid and ended up going to Harvard law school. When he graduated, he wanted to do something to give back to his community. Crime was at an all time high and he knew black people were the most likely people to be crime victims. So he became a prosecutor. “I thought I [was] going to go in as this undercover brother and make a difference from the inside,” he said.

But as a prosecutor, Butler’s biggest job was to put people behind bars, “And it turned out I was good at that,” says Butler. “I was this clean-cut black guy and most of the jurors were these older black people. They would just beam at me when I said my name is Paul Butler and I represent the government. They’d be like, you go boy. They’d almost do whatever I wanted”

Almost. Except when it came to petty drug cases. Even when it was very clear someone was guilty of a drug crime, juries came back with an not guilty verdict. Butler was confused, “Why would they let someone they knew was guilty of a drug charge go free?”

Then, one day, he was prosecuting a routine crack cocaine possession case.

“The defendant was a young, good looking African-American kid. And the defense was something like, ‘Yeah, the police caught me with the drugs, but they weren’t mine’,” said Paul, laughing. “I was like okay, for the law it doesn’t matter, it’s what’s called a strict liability crime. So you’re guilty. The judge even told that to the jurors.” Paul was sure he had this one in the bag.

“But then the jury came back with a big fat not guilty. I was like, Oh my god! What’s up?”

Paul waited outside the jury room. And as the jury filed out, he tried to talk to the jurors. “None of the black jurors would talk to me and then the only white woman stopped for a moment. I said, ‘What happened?’ She said, ‘We all knew he was guilty but he’s so young.’”

Even if the jurors thought the boy was too young, the law was still the law. Butler asked the more experienced prosecutors what was going on. It turned out it has a name: jury nullification.

When a jury nullifies, it finds a defendant not guilty, although the jurors may actually believe he is guilty. And because it’s illegal to retry someone, the person goes free. Jury nullification happens when jurors don’t agree with a law, or think there should be an exception.

For example, if someone assists a terminally ill spouse in pain with a suicide, it’s a murder according to the law. But often, juries will find these people innocent. And increasingly, juries are finding people with minor drug offenses innocent, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

The senior prosecutors Butler talked to hated jury nullification. They thought it weakened the legal system. But Butler couldn’t shake the feeling that these older black jurors were up to something important. He left the prosecutors office and when into academia. The first thing he wanted to study was jury nullification.

The History of Jury Nullification

Jury nullification dates all the way back to English common law. It was designed as a check and balance on the government’s power, and it has played a big role in American history. During the revolutionary war it was illegal to speak out against the British. But juries would just find the defendants innocent. And during prohibition, juries nullified to keep bootleggers out of jail.

But the history that really made Butler start considering the power of nullification was how it was used during slavery. In 1850 it was illegal to help a slave escape. But juries often refused to convict the defendants. According to Butler those nullifying jurors helped set up the conditions to abolish slavery. “What would you do?” asks Butler.

For Butler, it was an easy answer. Slavery’s wrong.

But jury nullification has a dark history too. Jeff Cramer is the managing director of Kroll Investigations and has tried at least 100 jury trials. “I don’t think anyone could really advocate for a system where the juries can really do anything they want to do,” he says.

Cramer says historically, juries have used nullification to do things we look back on as being right. But they’ve also used nullification to do things that we look back on as being really wrong.

The most infamous examples are from the civil rights movement. In August of 1955 two white men killed Emmett Till, a black 14 year-old who they said whistled at a white woman. The evidence was clear. Later, the two white defendants would even admit to the murder. But the all white jury found the white defendants innocent. That was nullification, too.

“The risk is people get away with murder,” says Crammer. “And they get away with murder because the juries in those cases regarded the defendants as more valuable than the victims. So if we allow jury nullification, it doesn’t work, system’s over. It’s broken.”

Contemporary Jurors

Shari Diamond is a professor Northwestern Law school. Jury deliberation is usually very private, but Diamond got an unusual level of access to study them in action. She’s observed hours and hours of juries deliberating. Her conclusion? Nullification doesn’t happen very much.

“No one disputes that juries take their work very seriously,” says Diamond. “The jurors will say I sure don’t agree with that law, but we don’t have a choice.”

Of course juries are a cross section of society, so they tend to have the same prejudices and sensitivities of a general population. But Diamond says you have to remember that in order to be on jury, you have to first get through a selection process. That weeds out people with biases, people who might nullify.

According to Diamond, “The jury is us, but perhaps a better us.” That better us nullifies only in rare circumstances, usually when our accepted morals don’t match up with the letter of the law. “One way of saying it is this a sort of safety valve,” says Diamond. “We tolerate it, officially it’s not the law, and there are in fact court opinions that say they have no right to do it. But of course, we build a system where the jury has the power to do it.”

Paul Butler, the prosecutor who was having trouble getting guilty verdicts, thinks it may be the most direct form of democracy we have. Twelve people, in a room, charged with coming to a single conclusion. And like any piece of democracy, like voting, people will sometimes make bad decisions.

He left the prosecutors office and became a professor at George Washington University [note: Butler is now a professor at Georgetown University Law Center]. Butler now believes those jurors who nullified in all those drug cases were on to something. “There are more blacks under criminal supervision now, than there were slaves in 1850,” says Butler.

Butler thinks drug laws are to blame for those high incarceration numbers. Statistically, there are fewer black drug users, but more blacks in prison for drugs.

So just like the jurors nullified the fugitive slave laws, Butler thinks modern jurors should nullify drug laws. “Sometimes the law really is unfair and sometimes jurors really should say people are not guilty, even if they committed the crime, especially if it’s a drug case, because the drug laws are selectively enforced and I don’t think it’s fair. So if a citizen has a power then she should use it.”

Keeping The Secret

Now despite the role nullification plays in our justice system, chances are you haven’t heard of it. And there’s a reason for that.

Most people in the legal system think juries shouldn’t nullify. It’s too dangerous to put so much power in the hands of just twelve people. Still they can’t take away jurors ability to nullify without taking away other basic rights enshrined in the Constitution.

But there are three ways the legal system tries to discourage nullification.

First, as a juror, you take an oath that says you will uphold the law. Second, defense lawyers aren’t allowed to tell a jury to nullify. Third, most judges give instructions to a jury that basically tell them that they must find a defendant guilty if they broke the law. So juries may be able to nullify, but the system is set up to hide that.

But some activists are working to spread the word about nullification.

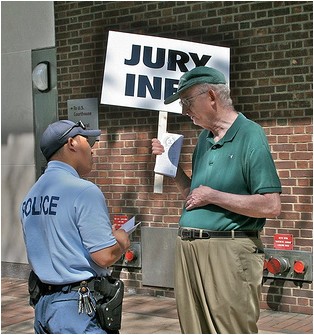

Julian Heicklin describes himself as, “the biggest pain in the ass in the world.” He’s a small, older man with a lot of big opinions. Heicklin is a member of the Fully Informed Jury association, a mostly libertarian group. Their goal is to make sure jurors know that they can nullify.

Heicklin stands outside courtrooms handing out literature and talking to people. Heicklin thinks nullification is a good strategy for all kinds of laws he sees as unfair, including gun laws.

In August of 2011 the US government charged Heicklin with jury tampering– a serious offense. The case got a lot of attention. Especially when the judge denied Heicklin a jury trial, because, after all, it would be another opportunity for him to tell jurors how to nullify.

But if courts want to keep this jury nullification thing on the down low, then Heicklin says, the joke has been on them, “They made a national issue of this, they did something I could have never done by myself.” Heicklin says he is just a shabby old man with a few pamphlets, but by prosecuting him, the courts handed out “the biggest pamphlet ever.”

Since I spoke with Heicklin, the case against him has been dropped. But he plans to be outside those courtrooms again soon, for better, or worse, making sure the secret power of nullification is a little less secret.