A kind of death occurred at noon on Tuesday, April 23 at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Mark Epstein, the chairman of the school’s Board of Trustees, had called a meeting for students and faculty just six hours before. He stood at the front of the school’s Great Hall—the hall where Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass gave visionary progressive speeches, where the NAACP held its very first meeting, and where Susan B. Anthony had an office—and announced that the school would begin charging tuition of its undergraduates for the first time in over 150 years. That night, students staged a candlelight vigil while faculty wept over drinks.

Peter Cooper, the founder of the school, was the son of an impoverished hatmaker. He never received a formal education. He later wrote, “I formed a very resolute determination that if I could ever get the means, I would build an institution and throw its doors open at night so that the boys and girls of this city, who had no better opportunity than I had to enjoy means of information, would be enabled to improve and better their condition.” A series of inventions, including the I-Beam and Jell-O, made Cooper a wealthy man. He fulfilled his resolution and opened the Cooper Union in 1859.

Cooper constructed the school’s Foundation Building with an empty shaft for another as-yet unfinished invention: the elevator. When the elevator was finally installed, it lifted passengers to the pinnacle of the city. The building stood as the tallest in all of Manhattan and symbolized the school’s radical inversion of social hierarchy. At the time, most institutions of higher learning exclusively admitted white males of means. But the Cooper Union awarded degrees completely free of charge to women, immigrants, and other members of society’s periphery. Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate and philanthropist, was a major early funder of the school. Like Peter Cooper, Carnegie believed that “education should be as free as air and water.” The school hummed on the promise that humans have the right to an education, just as we have the right to breathe.

Perhaps Peter Cooper’s idealism seems quaint in 21st century America. Perhaps the assertion that a spattering of aspiring creatives deserves a free college education sounds like entitlement. Yet no institution of higher learning embodies the ideal of accessible education more than the Cooper Union did. To deride that ideal in this moment of trillion-dollar student debt and skyrocketing tuition is excessively cynical. College sticker prices perpetuate the American wealth chasm and make the American dream—that hope that talent and hard work can forge success regardless of inborn privilege—seem a naive fantasy.

I attended the Cooper Union School of Art from 2005-2010. The education I received there felt handmade, bearing the love and imperfections that accompany handmade objects. The facilities were often ramshackle and the classes often unstructured, but the absence of student debt created space to pursue knowledge for its own sake. Granted this precious gift, we students pushed ourselves and one another with a rambunctious thirst. Grades didn’t matter; ideas did. We worked, we drank, and then we worked some more. I often slept under my studio desk while artists around me worked till dawn.

This morning, three years after graduating, I sit in a cooperative house with Christhian Diaz, one of my best friends and another Cooper Union alumnus. We sip coffee and he shows me new photographs of grassy fields and protests. He tells me about arriving at the Cooper Union as a broke undocumented immigrant. He tells me how he confessed his plight to a professor. The professor hired him on the spot as an assistant, despite not needing help. This was the promise of the Cooper Union: we would support each other in our pursuit of knowledge and art, regardless of money.

Christhian protests tuition at the Cooper Union. The banner he carries had many lives. I sewed it as a recreation of a suffrage banner for an exhibit at the Cooper Union about the early Women’s Rights movement. Its message proved apt for the tumult that later occurred at the school.

But money caught up with this rare bloom of idealism, as tends to happen. The school took out a $175 million loan to help construct a new building in 2006. Then the financial crisis hit. In 2011, a new college president proposed charging tuition to dam the school’s $16 million annual losses. Students, alumni, and faculty revolted, arguing that the full-tuition scholarships were the school’s one priceless commodity. They staged occupations and penned protests and presented the president with a “Happy Resignation Day” cake. And then came Tuesday’s last-minute meeting. Tuition appears sealed.

The new building is a useless atrium encased in a silver skin. If the school’s Foundation Building symbolizes the progressivism of the 19th century, the new one reflects the superficial greed of the 21st. The allure of a glittery and expanded infrastructure blinded the Board of Trustees from recognizing the hazards of loans and hedge fund investments. Panting to keep up with our ever-expanding neighbors NYU and Columbia, the school’s richly compensated leaders took foolhardy risks. Now, lower and middle-class students must pay for those leaders’ mistakes. Sound familiar? Tuition at Cooper Union is symptomatic of the bigger trend of transferring liability from those at the top to those at the bottom, of which the gold-parachute-lined and regulation-thin 2008 bailout is another egregious example.

Niki Logis, the terrifying and brilliant Cooper Union professor of sculpture, instructed my freshman 3D Design class to make art as though our hair was on fire.

“HAIR ON FIRE! HAIR ON FIRE!” I remember her barking on at least one occasion.

Flaming hair is the level of urgency demanded to be an artist and an idealist. Letting go of both artistry and idealism is easy, but the Cooper Union bucked cynicism—and realism, perhaps—to add oxygen to those flames. Its commitment to education as a right is an anachronism today. Yet relics like this school move our democracy forward and keep its spark alight.

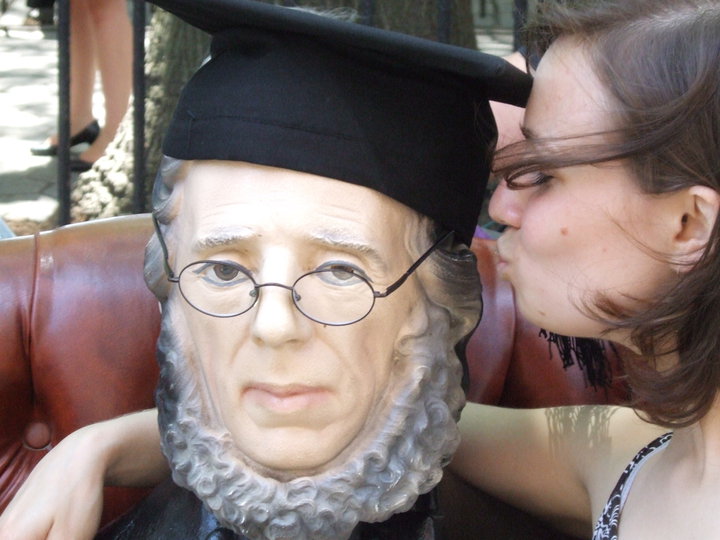

Rina Goldfield lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. She teaches art and other subjects to children and adults. She sporadically makes paintings and drawings. The photo above is of her on her graduation day from the Cooper Union, kissing a sculpture of Peter Cooper in gratitude.