The recent media spin on dwindling executions in the U.S. focuses on the refusal of European countries to provide the lethal chemicals needed to put the condemned to death. This blithe story of “supply and demand” rests on two misleading assumptions: it presumes (1) that most states in the U.S. are clamoring to conduct executions, and (2) that EU resistance is (at least if one was to trust a recent FOX news broadcast) somehow a call to American “execution independence.”

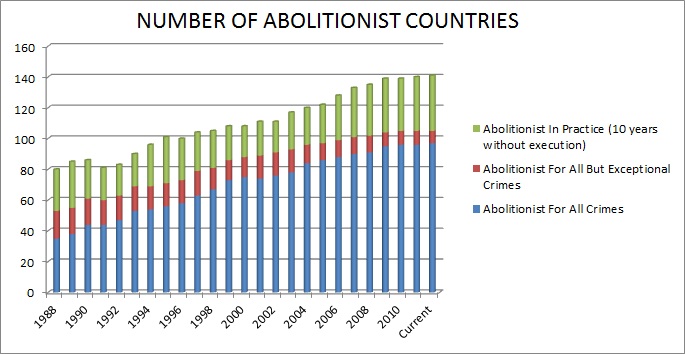

But a recent report from Amnesty International provides the necessary global context for understanding worldwide decline that is largely absent from the majority of major media accounts in the U.S. Beyond the EU’s refusal to provide the fix needed for lethal injections to commence, there have been radical changes that inescapably change the way we ought to talk about it. Consider this: by the beginning of 1980, only 20 countries had abolished the death penalty. Today, this number had nearly quintupled—in the last thirty years, 97 nations abolished the death penalty for all crimes and 140 had ceased conducting executions for at least ten years.

Why has this momentous change occurred?[1] First, despite struggling economies, the assimilation of international human rights norms calling for the worldwide abolition of the death penalty is an unwavering prerequisite for EU membership. The result has been widespread abolition, especially among new former Eastern and Soviet Bloc countries. Yet it is not simply a story of “procedural abolition”—the EU has engaged in aggressive diplomatic efforts, including training for anti-death penalty lawyers and the funding of empirical research to study the administration of the death penalty in countries that continue to retain it. Of course, the story of the path to abolition in South America and Mexico is different. To be sure, global commerce and the adoption of numerous human rights conventions is an important part of the story that cannot be underestimated. Yet a combination of other factors, including the fall of authoritarian regimes, the rise of anti-death penalty religious imperatives, and the creation of national penitentiary systems have played a major role in understanding accelerated abolition in the Global South.

What about the story of the U.S as a stubborn retentionist nation that is implicit in so much of the recent national media coverage over the EU’s blocking the importation of lethal drugs? Although there were 39 executions in 2013 and 77 death sentences imposed in 2012, bringing the total number of persons on death row in the United States to 3,108, the number of death sentences and executions is in steady decline. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, there was a high of 315 death sentences in 1996 and 98 executions in 1999, the number of death sentences imposed today is at an all-time low. Furthermore, eighteen of the fifty states in the U.S. have abolished the death penalty, and two more states have not executed anyone since the Supreme Court lifted a nationwide death penalty moratorium in 1976. Three U.S. states—Texas, Virginia, and Oklahoma—account for the majority of executions carried out since 1976, and 85% of American counties have not been responsible for a single execution since 1976. Contrary to the tale of a so called “retentionist nation,” the death penalty as practiced in the U.S. today is a phenomenon of an increasingly shrinking minority of local legal regimes.

How is the EU relevant? One particularly persuasive explanation involves the recent scandals involving innocence and wrongful death sentences. In an important book, The Decline of the Death Penalty and the Discovery of Innocence, Political Scientist Frank Baumgartner and his colleagues make a strong empirical case that the dominant theme in contemporary American popular discourse on capital punishment is innocence and the consequences of wrongful capital sentences. One of the primary organizations dedicated to addressing the consequences experienced by exonerated death row survivors in the U.S. is Witness to Innocence. In 2006, the EU created the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR), a group that has played an instrumental role in supporting death penalty abolition and has provided substantial financial support and resources to Witness to Innocence. Indeed, the EIDHR was one of the organization’s 10th anniversary honorees.

One last word on the growing influence of the EU and the global abolitionist movement: It is well documented that China is the world’s leading executioner; putting to death in secret thousands of people every year. While China’s death penalty is likely to go nowhere anytime soon, it may be that EU diplomatic efforts have influenced the Chinese government to enact the most radically transparent and restrictive changes to its death penalty in the country’s long and barbarous history. The Chinese federal government has adopted Rules to Exclude Illegal Evidence in Criminal Cases and Guidelines to Scrutinize and Analyse Evidence in Capital Cases, the country’s first formal attempts to provide defendants in death penalty cases due process protections. By early 2011, China’s President, borrowing from the U.S. Constitution’s restriction on cruel and unusual punishment, ordered the country’s legal system to adopt its own regulations, The Eighth Amendment to the Criminal Law. This new law proposed unprecedented steps to shorten the reach of executions by formally limiting the number of crimes punishable by death, and by narrowing the death eligibility of defendants over the age of 75. In a move doubtlessly inspired by the U.S., the President also proposed the goal of adopting lethal injection over shooting as the preferred method of execution.

Many of my own students struggle to talk about legal issues from a “global” perspective. The death penalty is an excellent case for doing precisely this kind of teaching, and the resources on the internet are voluminous. Students and concerned citizens need to begin with this fact: The U.S. is a distinct minority among the world nations, and the overwhelmingly majority of the more than 3,000 U.S. counties have virtually abandoned capital punishment altogether. What about the more accurate story of a few stubborn death penalty active locales? Unsurprisingly, these are the counties that have the most racially unjust and under-resourced systems of indigent defense in the nation. That is to say, these locales operate broken systems that are chillingly similar to Chinese locales. According to Criminologist Michelle Miao, who has conducted extensive empirical research on China’s death penalty, national legal elites have limited the number of death eligible crimes but have a divisively, pro-death political climate and provide few legal resources to the accused (e.g., See Harris County, Texas). In spite of sweeping national reforms, Miao shows that implementation has largely not occurred at the local level in China. Yet the very fact that we are discussing the possibility of death penalty abolition—most stunningly, in China (!)—is a clear sign that the European-led global struggle to abolish the death penalty has been remarkably successful. Indeed, it has forever altered the debate.

[1] To learn a more complete answer to this question, I strongly recommend reading Roger Hood’s latest edition of his incomparable volume, The Death Penalty a Worldwide Perspective.

Image: Amestyusa.org

Benjamin Fleury-Steiner is Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at the University of Delaware and a member of Life of the Law’s advisory panel.